At all times, encoding the Didion perspective, there has been her famously elegant, yet somehow cockeyed, prose-the world seen through cracked crystal. She conveyed her judgments inductively, early on, and then, in later years, more explicitly, as though stripping the insulation from a wire.

” Soon after, we get something like the credo of a thirtysomething Didion’s highly subjective brand of journalism: “I admire objectivity very much indeed, but I fail to see how it can be achieved if the reader does not understand the writer’s particular bias.”ĭidion has since spent a long career bringing her particular bias to subjects as diverse as El Salvador and Martha Stewart, marital grief and the Hoover Dam, frequently uncovering details that others had missed, revealing that what had seemed peripheral was in fact central. Cool, controlled, obsidian-sharp, its core of self-assurance wrapped in gauzy diffidence, engaged even (or especially) by what repels it, this voice greets you from the first acerbic sentence of the first piece, circa 1968, in Joan Didion’s new collection of old essays, Let Me Tell You What I Mean: “The only American newspapers that do not leave me in the grip of a profound physical conviction that the oxygen has been cut off from my brain tissue, very probably by an Associated Press wire, are. The voice was there almost from the beginning.

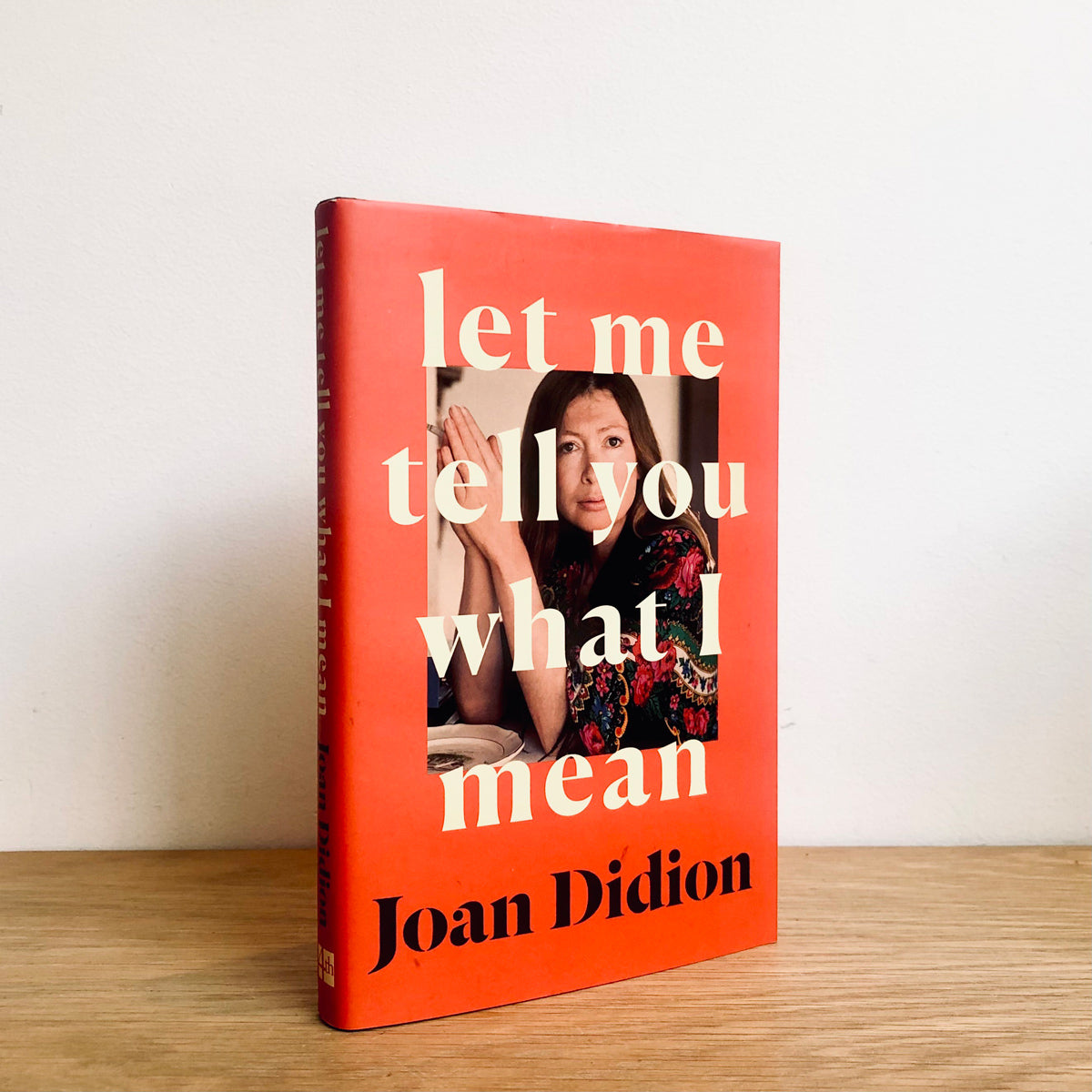

Let Me Tell You What I Mean, by Joan Didion (Knopf, 192 pp., $23)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)